| Source | Article from „¯ycie Warszawy” |

| Event referred to | Rise of EEC |

| Technological characteristics | Type of file: image

Extension: *.jpg

Dimension:

|

| Description of the source | Kind of source/: Newspaper article

Origin of the source: Archive

Language: Polish

Copyright issues: full availability

|

| Contextualisation of the source | The article describes the situation of European trade connections. The author thinks of advantages and disadvantages of acceding to the common market or to the free trade area by Great Britain. In the polish author’s opinion better solution would be acceding to the free trade area. |

| Interpretation of the source | “Zycie Warszawy “ was more objective than other polish newspapers that time. The way of thinking was pro-west what was very unusual because Poland was in communistic block. The authors thinks of advantages and disadvantages of two possible ways to go. |

| Original Contents |

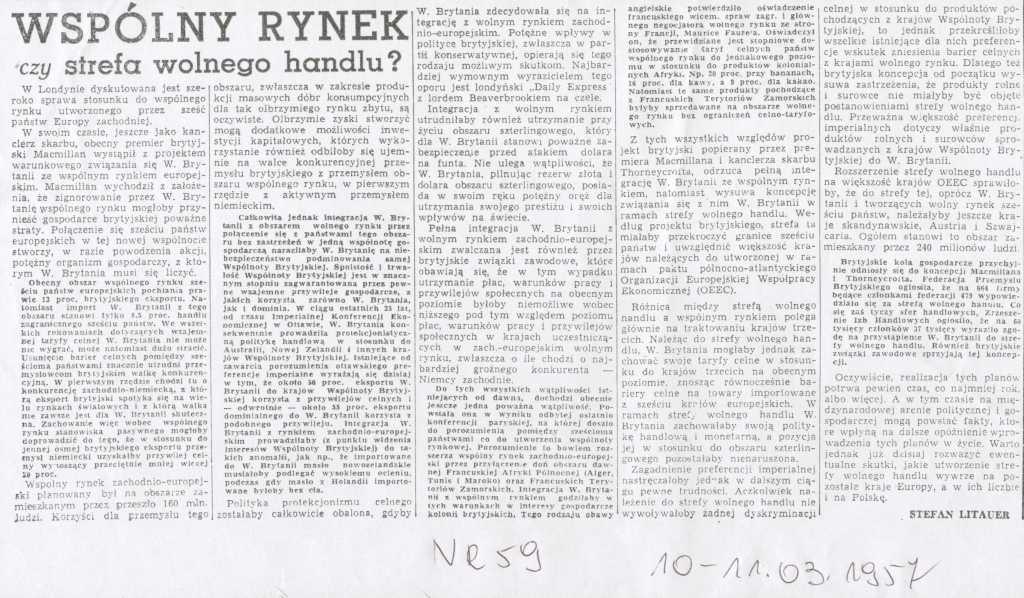

WSPÓLNY RYNEK czy STREFA WOLNEGO HANDLU?

„¯ycie Warszawy”, Nr 59, 10-11.03-1957r.

W Londynie trwa dyskusja na temat stosunku Wielkiej Brytanii do wspólnego rynku tworzonego przez szeœæ pañstw Europy zachodniej.

Jedn¹ ze stron jest premier brytyjski Macmillan, który uwa¿a, ¿e warto warunkowo zwi¹zaæ siê ze wspólnot¹, by zapobiec stratom gospodarczym wynikaj¹cych z pe³nej integracji.

Wœród argumentów przez niego przytaczanych, pojawia siê fakt, i¿ utworzenie wspólnego rynku utrudni przemys³owcom brytyjskim konkurencyjn¹ walkê.

Mimo ¿e korzyœci dla gospodarki i przemys³u z planowanego na obszarze zamieszka³ym przez 160 milionów ludzi otwarcia rynków wydaj¹ siê byæ oczywiste – nowe rynki zbytu, uprzywilejowana wymiana handlowa, to jednak w¹tpliwoœci wzbudza fakt, i¿ brytyjski przemys³ mo¿e podupaœæ z racji silnej konkurencji ze strony niemieckiej.

Co wiêcej, integracja gospodarcza z pañstwami europejskimi mog³aby zagroziæ spoistoœci i trwa³oœci Wspólnoty Brytyjskiej, w której sk³ad oprócz Wielkiej Brytanii wchodz¹ tak¿e miêdzy innymi Australia i Nowa Zelandia. Wymianê handlow¹ miêdzy tymi pañstwami obejmuj¹ liczne przywileje celne, Wielka Brytania prowadzi wobec nich politykê protekcjonizmu. Brytyjczycy nie chc¹ dopuœciæ do sytuacji, ¿e mas³o nowozelandzkie bêdzie dro¿sze od mas³a holenderskiego.

Oczywiste jest, ¿e w razie wejœcia Wielkiej Brytanii do wspólnoty, sytuacja ta by³aby obalona. Jeœli Wspólnota brytyjska – tzw. obszar szterlingowy – przesta³by istnieæ, Wielka Brytania móg³aby straciæ swój presti¿ i dogodn¹ pozycjê na arenie miêdzynarodowej oraz zabezpieczenie przed atakiem dolara na funta.

Ponadto, integracji ze wspólnot¹ nie chc¹ brytyjskie zwi¹zki zawodowe, które boj¹ siê zrównania zarobków, warunków pracy i przywilejów spo³ecznych z pañstwami Europy zachodniej, gdzie s¹ one mniej komfortowe.

Ostatnim elementem, który móg³by godziæ w interesy Londynu, jest podpisane krótko wczeœniej w Pary¿u porozumienie miêdzy pañstwami wspólnoty zak³adaj¹ce wejœcie do strefy przywilejów celnych pañstw Francuskiej Afryki Pó³nocnej, co zagra¿a³oby interesom kolonii brytyjskich.

Dlatego premier Macmillan odrzuca pe³n¹ integracjê na rzecz zwi¹zania siê Wielkiej Brytanii ze wspólnym rynkiem w ramach strefy wolnego handlu. Strefa ta, oprócz szeœciu krajów, mia³aby uwzglêdniæ wiêkszoœæ pañstw nale¿¹cych do dzia³aj¹cej w ramach paktu pólnocnoatlantyckiego OEEC (Organizacji Europejskiej Wspó³pracy Ekonomicznej).

Dziêki takiemu rozwi¹zaniu, pozycja Wielkiej Brytanii w stosunku do obszaru szterlingowego pozosta³aby nienaruszona, gdy¿ Londyn móg³by zachowaæ swoje stawki celne wobec krajów trzecich, znosz¹c jedynie bariery celne na towary importowane z szeœciu krajów europejskich.

Mimo to istniej¹ pewne zastrze¿enia. Handlowcy obawiaj¹ siê, ¿e postanowienia o strefie wolnego handlu przekreœl¹ ewentualne korzyœci, jakie mog³aby uzyskaæ Wielka Brytania i kraje Wspólnoty brytyjskiej z koncepcji wspólnego rynku. W¹tpliwoœci co do objêcia okreœlonych towarów stref¹ wolnego handlu dotycz¹ tak¿e produktów rolnych i surowców.

Ponadto, rozszerzenie strefy wolnego handlu na wiêkszoœæ krajów OEEC sprawi³oby, ¿e w jej obrêbie mieszka³oby 240 milionów ludzi.

Jednak bez wzglêdu na te zastrze¿enia, koncepcja Macmillana komentowana jest w Wielkiej Brytanii bardzo entuzjastycznie. Przystaje na ni¹ ponad 60% handlowców, a jedynie nieca³e 30% firm jest jej przeciwna. Pozytywnie reaguj¹ tak¿e zwi¹zki zawodowe.

Mimo wszystkich tych koncepcji i planów, prawdopodobnie i tak minie jeszcze przynajmniej rok, nim zostan¹ one zrealizowane, byæ mo¿e w tymczasie dojdzie do zmiany okolicznoœci, w jakich bêdzie rozwa¿any stosunek Wielkiej Brytanii do wspólnego rynku. Jednak warto ju¿ teraz zastanowiæ siê nad skutkami decyzji Londynu wobec innych krajów europejskich, w tym Polski.

|

| Original Contents (English Translation) | In London the discussion continues on the relation of Great Britain to the common market created by six states of western Europe.

One of the parties is the British Prime Minister Macmillan, who believes that it is right to conditionally bind with the community, in order to prevent economic losses resulting from a full integration.

Among arguments he quoted, is a fact that the creation of the common market will make competitive fight difficult for British industrialists.

Although the advantages for economy and industry resulting from the planned opening of markets in the area inhabited by 160 million people (such as new markets and privileged commercial exchange) seem to be self-evident, doubts arise about the fact that British industry could deteriorate due to a strong competition on the part of Germany.

What is more, economic integration with European states could threaten the solidity and continued existence of British Commonwealth whose members, apart from Great Britain, also include Australia and New Zealand. Commercial exchange between these states enjoys numerous customs privileges, thanks to British policy of protectionism. British do not want to allow a situation in which butter from New Zealand would be more expensive than Dutch butter.

It is self-evident that in the event of Great Britain’s entry to the community, this situation would be disrupted. If British Commonwealth – the so-called sterling area – ceased to exist, Great Britain could lose its prestige and its privileged international position as well as losing the protection against the attack of the dollar on the British pound.

Besides, British trade unions do not want the integration with the community, fearing that earnings, working conditions and social privileges will be levelled down to those in West European states, where they are less comfortable.

The last element which could threaten London’s business, is the agreement, signed shortly earlier in Paris between community members, providing for the states of French Northern Africa to accede to the zone of customs privileges, which would pose a threat to business of British colonies.

This is why Prime Minister Macmillan rejects the full integration in favour of tying Great Britain with the common market, within the framework of free trade area. This zone, apart from its six countries, would have to include most of OEEC member states (Organization of European Economic Cooperation), a body working within the framework of the North Atlantic pact.

Thanks to such a solution, the position of Great Britain in relation to the sterling area would remain intact, as London would be able to keep its customs duty rates applicable for third countries, abolishing only tariff barriers on goods imported from six European countries.

Nonetheless, certain reservations exist. Tradesmen fear that settlements about the free trade area will overshadow the possible advantages which could be obtained by Great Britain and countries of British Commonwealth from the idea of the common market. Doubts regarding the inclusion of certain goods into the free trade area concern also farming products and raw materials.

Besides, the enlargement of the free trade area into the most of OEEC countries would cause a situation in which that 240 million people would live within its boundaries.

However, irrespective of these reservations, Macmillan’s idea is commented in Great Britain very enthusiastically. More than 60% of tradesmen consent to it, and only slightly less than 30% of the firms oppose it. Trade unions also react favourably.

Despite all these ideas and plans, it will probably take at least a year before they are realized. It is also likely that the circumstances, in which Great Britain’s stance to the common market will be examined will change. Nevertheless, it is already worth reflecting on results of London’s decision in relation to other European countries, including Poland.

|